I woke up this morning with a fragment of a dream still clinging to me—something about connecting dots between unrelated books on my shelf. In the dream logic way of things, I was physically drawing lines between them with a piece of red string, creating this chaotic but somehow perfect web across my apartment (yes, I was doing the meme). When I opened my eyes, the image dissolved, but the feeling lingered: that sense that everything I've ever read or thought about exists in this single, messy constellation inside my head.

It's a comforting feeling, honestly. Like maybe my brain isn't as disorganized as I worry it is.

I've been thinking a lot lately about where ideas—actual original ones—really come from. Not in that mystical "the muse visits you" way that people love to romanticize, but in the more mechanical, systems-level way. What are the prerequisites for having a genuinely new thought? What invisible architecture has to exist in your mind before that moment of "holy shit, wait a minute..." can happen?

There's this concept I stumbled across recently called H(φ)—the complete set of theories, skills, and insights you must know before you can push into truly new territory in any field. In physics and math, H(φ) often refers to a system’s total energy or entropy, depending on the context. But I’ve been thinking about it more abstractly—as a metaphor for the hidden scaffolding of thought. It’s a fancy academic way of saying: you need to master all the building blocks before you can make the breakthrough.

I find this both deeply reassuring and slightly terrifying.

Reassuring because it suggests that originality isn't magic—it's accessible. It's the natural result of doing the work to understand what came before. Terrifying because it means there are no real shortcuts. If I'm missing even a single crucial element from that set of prerequisites, I might be permanently stuck on this side of insight, never quite finding what I'm reaching for.

When I think about some of my original ideas—I can trace the strange winding paths that led there. Books I read years apart that suddenly connected. Conversations that planted seeds. Observations that only made sense in retrospect. My brain was building the pyramid of prerequisites without me fully realizing it, until suddenly I was standing at the top, looking at a view I hadn't seen before.

This feels particularly relevant to me right now, this week before my birthday, when I'm doing that inevitable catalog of what I know and don't know, what I've done and haven't done. The older I get, the more I realize that what feels like "my original thought" is actually this peculiar alchemy—my specific, unrepeatable mixture of influences, experiences, readings, conversations, mistakes, and obsessions (you already know I’m heading towards mental models).

Maybe that's what people mean when they talk about finding your voice. It's not really about style or tone—it's about recognizing the unique fingerprint of your mental constellation. The particular way your prerequisites fit together that nobody else could quite replicate.

The Hidden Architecture of Thought

I have this image in my head (I swear I'm not high as I write this—going on 5-months weed-free, actually!) of each of us walking around with these invisible mental architectures—these intricate structures built from everything we've absorbed. Like those MRI visualizations of neural networks, except they'd show not just physical connections but conceptual ones.

My architecture would reveal weird bridges between Bronowski's thoughts on human creativity and that one paragraph in a Susan Sontag essay I read in college that I think about at least once a week. It would show how a conversation I had with my dad when I was twelve somehow connects to my thoughts about capitalism. It would map all those browser tabs I never close because they're part of some nebulous "research" that my conscious mind hasn't fully articulated yet.

Your architecture would look completely different—not just in the content (though that too) but in the structural patterns. Some people build tall, narrow towers of deep expertise. Others (hello) create sprawling, interconnected webs with unexpected passageways between domains. Neither is better in any absolute sense—they just enable different kinds of insights.

What fascinates me is how these architectures determine what kinds of original thoughts we can have. You can't think a thought if you don't have the mental infrastructure to support it.

Take someone like Leonardo da Vinci. We marvel at his ability to connect art, science, engineering, and anatomy—but of course he connected them. In his mind, those weren't separate domains. His mental architecture had pathways between them that most of his contemporaries lacked. Not because he was superhuman, but because he'd built the prerequisites in multiple fields and—this is the crucial part—maintained the connections between them.

Or think about someone working at the edge of two fields today—maybe a biologist who's also deeply versed in mechanical engineering. They might see a solution based on how birds' wings work that pure engineers would miss, not because they're smarter but because their H(φ) spans two domains. Their mental architecture has doorways where others have walls.

Mental Models: The Lenses We Can't Take Off

Something I've been obsessing over for a while now—something that connects directly to this idea of prerequisite knowledge—is the concept of mental models. Those invisible frameworks that silently determine how we interpret everything.

I have this little equation I use as a shorthand for how our minds process reality:

P+D=MM(E+B+I)

The idea that our Perceptions (P) and Decisions (D) are the result of our Mental Models (MM) filtering and processing our Experiences (E), Beliefs (B), and Information (I).

What fascinates me most is that most of us aren't aware of our mental models. They're like contact lenses we've worn so long we've forgotten they're there. We don't experience raw reality—we experience reality as processed through these frameworks, these sets of assumptions and patterns that help us make sense of otherwise overwhelming complexity.

When I think about original thought in this context, it becomes even more intriguing. Because developing truly original ideas might require not just adding new knowledge but actually modifying these underlying mental models—or creating entirely new ones.

This is why it's so disorienting (and valuable) to read something that fundamentally challenges how you think. It's not just giving you new information—it's messing with the processor itself. It's changing the MM in my little equation.

I remember reading Lakoff and Johnson's "Metaphors We Live By" and feeling slightly dizzy afterward. They argue that metaphors aren't just linguistic flourishes but fundamental structures that shape how we think. We experience time as a resource that can be "spent" or "wasted" not because time is actually a commodity, but because we've collectively built a mental model that processes time through the metaphor of money.

That book didn't just add information—it changed how I processed information. It installed a new lens that I couldn't take off, even if I wanted to. And once that lens was in place, I started seeing metaphorical structures everywhere, from how we talk about arguments ("defending positions," "attacking weak points") to how we conceptualize love ("investing in relationships").

I think this is what makes building a truly unique mental architecture so powerful. It's not just about having knowledge others don't have—it's about processing knowledge in ways others don't. It's about having mental models that let you see patterns invisible to those using more conventional frameworks.

And the wild thing is, once you adopt a new mental model, you can't really explain to others what it's like to see through it. You can present the same information, but without the model, they won't process it the same way. You can tell someone about the metaphorical frameworks underlying our thought, but until that clicks as a mental model for them, they'll just nod politely while missing the profound implications.

This might be why truly paradigm-shifting ideas often face resistance. It's not just that people disagree with the information—it's that their existing mental models literally prevent them from processing that information the same way the originator does.

When I look at thought leaders I admire, I realize they're not just knowledgeable—they've developed unusual mental models that process common experiences in uncommon ways. They see the same world we all do, but through fundamentally different frameworks. That's what gives their insights that quality of being simultaneously obvious (once pointed out) and revolutionary (in that no one saw it before).

The challenge, then, in developing original thought isn't just accumulating prerequisites—though that matters enormously. It's being willing to revise or even discard mental models that have served us well, to adopt new frameworks that might initially feel uncomfortable or counterintuitive.

This is probably why intellectual growth often feels like a crisis. It's not just adding; it's transforming. It's not just learning new information but changing how we process all information.

Which brings me back to the H(φ) concept. Maybe the most important prerequisites aren't individual pieces of knowledge at all, but the meta-skill of recognizing and revising our own mental models. Maybe the ability to say "this framework I've relied on might be limiting what I can see" is itself the master prerequisite for original thought.

Mental models are something I think about often and I’ve written about them in the past. This is one of my most recent takes:

mental models for people who actually want to think

The Prerequisites I've Been Missing

I've been reflecting on the areas where my own thoughts feel frustratingly shallow or derivative—where I sense there's more interesting territory just beyond my reach, but I can't quite get there.

In most cases, I can identify specific prerequisites I'm missing.

My understanding of economic systems, for instance, has embarrassing gaps. I have these half-formed thoughts about market dynamics and incentive structures, but I lack the formal training to develop them beyond "interesting cocktail party speculation." There are economic concepts I've never properly understood—concepts that would likely unlock whole new ways of thinking about human behavior. That's a missing prerequisite I can identify.

I also realize I've developed mental blind spots from inhabiting certain social and intellectual bubbles. This is trickier to fix because these blind spots are, by definition, hard to see from the inside. My mental architecture has these comfortable rooms I return to again and again, without realizing I've stopped building new wings.

When I was younger, I absorbed ideas more promiscuously. I'd read anything, try to understand viewpoints radically different from my own, pursue intellectual crushes down wild rabbit holes. Now I notice myself becoming more selective, more efficient—which sounds positive but might actually be narrowing the range of possible connections.

Efficiency is the enemy of serendipity, and serendipity is often where the magic happens.

I'm starting to think that maintaining a capacity for original thought requires a deliberate inefficiency—a willingness to read things "just because," to have conversations with no agenda, to follow curiosities that might not "pay off." To keep building your mental architecture in unexpected directions even when it seems like you should be focusing on reinforcing what's already there.

Constellations Only You Can See

There's something deeply personal about all this. My H(φ)—the complete set of prerequisites I've accumulated—is mine alone. Even if someone else read all the same books and had all the same conversations (impossible, but as a thought experiment), they wouldn't make the same connections. They wouldn't notice the same patterns or be bothered by the same contradictions.

I'm realizing that this might be what we mean by perspective—not just our opinions or biases, but the unique topography of our mental space. The particular way knowledge arranges itself in our minds.

This is why truly original thinkers are so rare and valuable. It's not just that they're "smarter" in some generic sense. It's that they've built mental architectures that enable them to see constellations no one else can see. They've accumulated a set of prerequisites—through study, experience, observation—that allows them to make connections that remain invisible to others.

When I think about the thinkers and creators whose work moves me most deeply, this is what they share: not just intelligence or skill, but a perspective—a mental architecture—that lets them illuminate patterns the rest of us miss. They've done the work of mastering prerequisites across domains that don't usually speak to each other.

The Illusion of Originality

The deeper I get into this exploration, the more I've been wrestling with a troubling suspicion: what if there's no such thing as original thought at all? What if this entire conversation about prerequisites for originality is itself built on a flawed assumption?

Sometimes I stand in front of my bookshelves—over 600 books collected across years—and feel this strange vertigo. All these voices stretching back through centuries, millennia even, recycling the same fundamental human questions through different frameworks. Love, death, meaning, beauty, suffering. Homer wrote about them. So did Socrates. So did my favorite contemporary essayist last week on her Substack.

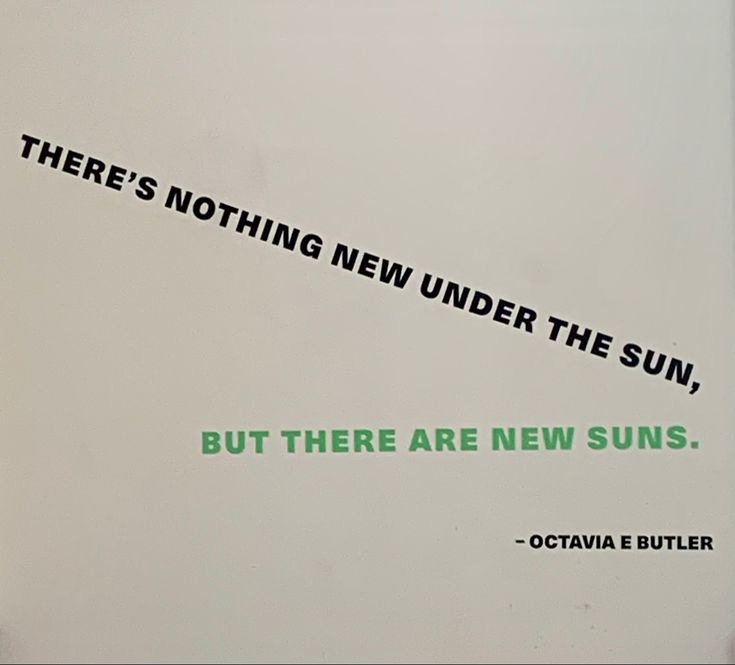

"There is nothing new under the sun." Those words from Ecclesiastes haunt me—not just because they're beautiful, but because they were written thousands of years ago and yet perfectly articulate this modern anxiety about originality. Their ancientness is precisely the evidence for their truth.

What if what I've been calling "original thought" is really just this peculiar alchemy of influence—taking the same ancient building blocks and arranging them in patterns that feel fresh only because they reflect the particular constellation of my experiences? Not creation but recombination.

Maybe we're all less like inventors and more like translators. We're translating timeless ideas into languages that make sense for our moment, our context, our particular mess of experiences.

If that's true, then the value isn't in the "newness" at all, but in the resonance. In finding ways to articulate ancient wisdom so that it feels immediate and alive to people right now. To say the old things in ways that make them felt again.

Maybe that's why we recognize truth when we encounter it—not because it's novel, but because it awakens something we already intuitively understood but couldn't express. That moment of "yes, exactly!" isn't discovery so much as recognition.

This changes everything about how I think about my own mental architecture. It's less about building toward some unprecedented breakthrough and more about developing a perspective distinctive enough to refresh these timeless ideas, to make them vivid again through the particular lens of my experience.

There's something weirdly comforting in this. The pressure to be "original" dissolves when you realize you're part of this vast, ongoing conversation across time. You don't have to invent the language—you just have to speak it in your particular accent, with your particular cadence, emphasizing the bits that matter most to you.

The Alchemy in My Own Head

Coming back to my own small corner of thinking, I'm trying to be more conscious of what I'm adding to my mental architecture. What prerequisites am I building or neglecting? What connections am I nurturing or allowing to atrophy?

I know that my best writing emerges not when I'm trying to be original, but when I'm allowing the unique constellation of my influences to speak through me. When I'm not fighting the particular shape of my mental space but embracing it, exploring its odd corridors and unexpected intersections.

This is why I read so widely and sometimes struggle to explain my reading patterns to others. That random book on the Bronze Age collapse isn't a non sequitur to me—it connects to something I'm thinking about regarding how ideas spread, which connects to my interest in taste and discernment, which connects to my thoughts on Bronowski and human potential. The connections might not be immediately obvious to anyone else, but in the architecture of my mind, they form a coherent pathway.

And maybe that's the point. It's not about originality at all—it's about authenticity. About allowing yourself to process these ancient, recycled ideas through the specific, unreproducible filter of your lived experience. To say, "Here's how these perennial questions look from where I stand, with my peculiar collection of scars and wonders."

It's why, when someone says something like "there are no original ideas left," I find myself both agreeing and disagreeing. True, almost any individual idea has probably been thought before in some form. But the specific constellation of ideas that emerges from your particular mental architecture? The particular way you translate the timeless? That's as unique as a fingerprint.

Building While Exploring

As I approach this birthday milestone, I'm holding these two seemingly contradictory thoughts: I need to be more deliberate about filling gaps in my prerequisites, about building my mental architecture in areas I've neglected. And simultaneously, I need to allow more time for aimless exploration, for the kind of mental wandering that leads to unexpected connections.

I need to build and explore at the same time. To strengthen foundations while remaining open to detours. This is actually one of the reasons I decided to start the thoughts from down the rabbit hole series. I figured, if I’m going to follow my curiosities, I might as well share what I’ve learned. Plus, it kind of forces me to “document” my “research” which inevitably comes in handy at later dates.

There's a vulnerability in admitting this—in acknowledging that my thinking has blind spots and gaps, that there are prerequisites I haven't mastered. But there's also a strange comfort in it. The path to more vibrant thinking isn't mysterious or dependent on creative genius. It's about the patient work of building mental infrastructure, of developing my unique constellation of knowledge and keeping the connections between points alive and buzzing.

So maybe that dream about red string connecting my books wasn't so random after all. Maybe it was just my subconscious reminding me that the value isn't in individual volumes, but in the web I create between them. That meaningful thought emerges not from isolated brilliance but from the patient cultivation of connections that only I would think to make.

And as I drift off to sleep tonight, I'll try to remember: the goal isn't to build the biggest or most impressive mental architecture. It's to build one that's distinctly mine—one that allows me to translate ancient wisdom through a lens no one else possesses, to rearrange timeless elements into constellations invisible to others, and to describe those constellations in ways that might, just might, allow others to glimpse them too.

Thanks for reading with me ツ

You always write very thoughtful interesting & thought provoking essays.

Alas, thought provoking also means I'd have to spend more time thinking about and composing a reply, which I almost never have the energy to do (work + home & RL uses up most of what i got, the rest is spent decompressing) so I may NEVER leave you a thoughtful comment that properly engages with your writing, just know people are out here reading & appreciating even if we're not responding the way you'd probably like & definitely deserve.

I love this and am so inspired. I was first exposed to mental models through Naval Ravikant years ago and can’t wait to read the rest of your essays on this. ☺️