Being wrong is supposed to feel bad. That’s how we were trained. From early education through corporate culture, wrongness is treated like a red mark on a permanent record. Get the wrong answer, lose points. Make the wrong call, lose credibility. In that world, truth isn’t discovered through iteration; it’s revealed through authority. There is one right way, and anything else is a deviation.

But what if that framing is completely backwards?

What if being wrong—publicly, repeatedly, and with precision—is not a weakness, but a superpower? What if wrongness is the tool that separates people who merely perform intelligence from people who actually grow?

Useful wrongness is exactly that: wrongness that reveals signal. Not all errors are equal. Some dead-end you. Some open doors. The key is knowing the difference.

We’re conditioned to see wrongness as shameful, so we avoid it. And when we can’t avoid it, we reframe it. We dress it up. We rationalize. We delay admitting fault until there’s no social cost left. The higher your status, the more tempting it becomes to retrofit your mistake as foresight.

But this creates a system where the only people who "learn" are the ones with nothing to lose. Which means those with the most power and the most influence are often the least in contact with reality. Their identity—and often their livelihood—depends on not being wrong. So they double down, dig in, or change the subject.

And yet, the fastest path to actual wisdom is learning to love the signal inside your own mistakes.

That’s all the scientific method ever was: institutionalized wrongness. You form a hypothesis and then try to break it. Truth, in science, doesn’t come from consensus—it comes from exposure to failure. From ideas surviving contact with reality. It’s the oldest—and most resilient—truth-finding system we have. Because it builds by subtraction. It sharpens by error.

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool." — Richard Feynman

Feynman didn’t just accept this. He relished it. He understood that the joy of science wasn’t in being right, but in discovering where you were wrong and learning something new. His entire ethos was built around intellectual honesty, even when that honesty made him look naive, foolish, or slow to catch on. Because he knew that the only real failure is refusing to see what reality is trying to teach you.

Feynman revolutionized not just physics, but the approach to scientific inquiry. He was a Nobel laureate who contributed to quantum electrodynamics, yet he famously said, "I think it's much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong." That quote wasn’t a humble-brag—it was his compass. His entire method centered around curiosity that overpowered ego.

In his book "The Pleasure of Finding Things Out," he talks about how the process of exploration is the real payoff. Not the prize at the end. Not the recognition. But the moment you realize something you believed is wrong, and you now have the chance to revise the model. It’s a dopamine hit for people who care about truth more than status.

This is also why Feynman hated pompous academic culture. He criticized systems that rewarded jargon over understanding and mocked those who pretended to know more than they did. One of his most quoted jabs is: "Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts." Not because he didn’t respect expertise, but because he believed in keeping experts honest. Science, in his mind, was never settled. It was always provisional, always one experiment away from collapse.

And that made him dangerous in all the right ways.

He brought this mindset even outside the lab. As part of the Rogers Commission investigating the Challenger disaster, Feynman cut through layers of NASA bureaucracy with one simple act: he dropped a piece of rubber O-ring into a glass of cold water and demonstrated its failure in real-time. No theory. No credential wars. Just evidence. Just contact with reality.

Feynman didn’t need to be right first. He just needed to test.

That’s what made him different. That’s what made him right more often than most.

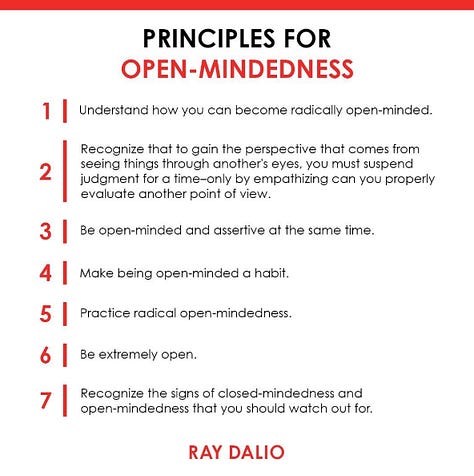

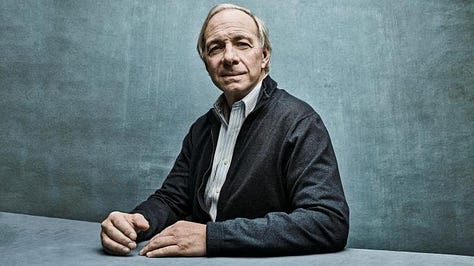

Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, took this principle and systematized it. He built an entire organization around what he called radical transparency and thoughtful disagreement.

At Bridgewater, making a mistake is not only tolerated—it’s expected. The culture is designed to extract insight from every error. Every meeting is recorded. Every idea is rated. Every disagreement is surfaced.

Why? Because truth emerges from tension, not politeness.

Dalio created a feedback loop that turns wrongness into signal. If someone flags a mistake you’re making, you don’t defend yourself. You thank them. Because they just helped you improve your model of reality. In that context, being wrong is a contribution. It’s not embarrassing; it’s essential.

"Pain + reflection = progress." — Ray Dalio

Most people run from the pain part. They’ll read another book. Start another productivity system. Anything but confront the raw edge of where they’re misaligned with reality. But Dalio made pain part of the process. And Bridgewater’s track record—for decades—speaks for itself.

This approach requires something most cultures do not teach: a separation between ego and ideas. In Dalio’s system, your identity is not at stake when your hypothesis gets torn apart. You don’t have to be right to matter. You just have to be willing to engage with what’s true.

Imagine what the world would look like if more people operated that way.

The difference between people who grow and people who perform is simple: strategic curiosity.

People who grow ask better questions. They look for friction. They want feedback. They’re not afraid to look stupid, because they know that the fastest way to stop being stupid is to find out where you are.

People who perform avoid all of that. Their goal is to appear competent, not become competent. So they stick to safe territory. They talk like TEDx speakers. They weaponize credentials. And when they get something wrong, they get defensive, because the error is now a threat to their identity.

This is why you see so many intelligent people stagnate. They stop updating. They start performing. And performance kills growth.

Useful wrongness only works if you’re willing to subordinate your image to your evolution. That’s the ask. You have to give up being seen as smart in order to actually become wise.

Most people can’t do that. It’s too costly. It requires a level of ego death that the culture doesn't reward. Especially now. We live in a culture that rewards certainty and outrage. Social media favors the loudest voice in the shortest time—so people learn to posture instead of revise. They fear reversals because reversals look like weakness in a performative environment. But real builders? They revise in public. They iterate in daylight. They trade being “right” for being ready to improve. And that’s why they win in the long run—they learn faster, iterate better, and compound truth over time.

They don’t fear being wrong. They fear calcifying.

And once you realize how much information is trapped inside your errors, you stop avoiding them. You start mining them.

That’s the real unlock.

Not being right.

Being wrong in a way that moves you forward.

Every breakthrough—scientific, personal, or cultural—begins with someone brave enough to say, “I got that wrong. Let’s try again.”

That’s how systems evolve. That’s how people grow. That’s how anything real gets built.

I’m on board !