I'm looking at this photograph that shouldn't exist1: a woman from a centuries-old painting about vanity, transplanted into a 1970s home office, still holding her mirror, still gazing at herself with that same absorbed attention. I've been making these lately—stealing classical figures from their proper contexts and dropping them into spaces they don't belong, a strange little artistic compulsion that started as play but has become something more like therapy. But what gets to me about this particular image isn't just the visual oddity of it, but how naturally she seems to inhabit this domestic space, how unself-conscious she appears surrounded by the debris of modern real life.

Something about seeing her there, naked and unashamed in the middle of ordinary life, made me realize how strange our relationship with ourselves has become—and how we may have completely misunderstood what vanity actually is. We've turned it into this shameful thing, this moral failing, when maybe what she's really doing is something far more fundamental—tending to herself with the same careful attention we give to anything we consider important. When did we decide that we weren't worth that kind of attention? When did we decide that looking at ourselves became a moral failing? When did we stop thinking of ourselves as our own most important project?

There's something almost violent about the way we've weaponized the word "vanity." We've turned it into something ugly, a way to shame anyone who dares to find themselves worth looking at. But sitting here, thinking about this image, I realize I've been carrying around a relationship with my own reflection that's far more complicated than simple self-love or self-hatred.

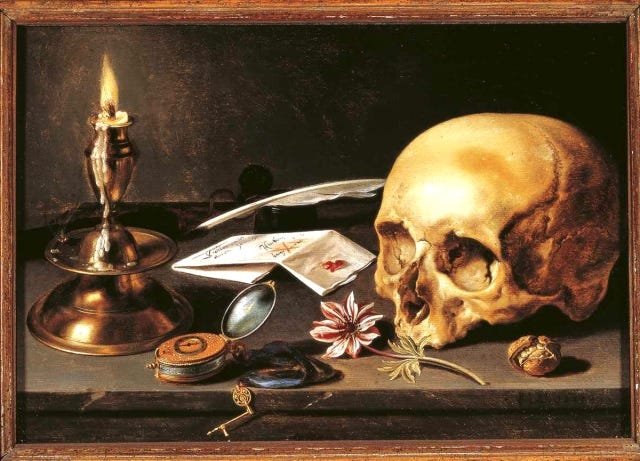

The original vanitas paintings—those Dutch still lifes with their skulls and wilting flowers—were supposed to remind us that beauty fades, that life is brief, that we shouldn't get too attached to appearances. Memento mori, they whispered. Remember you must die. But what strikes me now is how much energy those painters put into making their warnings beautiful. They spent months perfecting the way light caught on a soap bubble, the exact curve of a dying tulip. There's something almost perverse about it—using exquisite technique to argue against caring about exquisite things.

There's this moment that happens sometimes when I haven't looked in a mirror for a while—maybe I've been deep in work, or sick, or just living inside my head—and I catch my reflection unexpectedly. For just a split second, I don't recognize the person looking back at me. It's not that I look different, exactly. It's more like I've forgotten that I have a face at all, that I exist in physical space, that this particular arrangement of features is how I move through the world. These moments always surprise me, like finding money in an old coat pocket—a sudden reminder that I have a body, that consciousness somehow got housed in this particular flesh.

Who is that? I think, staring at this stranger who is somehow me.

The woman in this photograph has that same quality of patient self-regard, but without the shock of recognition. She's clearly spent time with herself, this woman who exists impossibly between centuries. She holds the mirror not like she's discovering herself, but like she's checking in with an old friend. There's something almost maternal about it—the way you might look at a child you're responsible for raising. She's naked, yes, but she's also somehow domestic. She's not in some ethereal realm of pure vanity; she's in the middle of someone's real Tuesday afternoon, taking a moment to simply look at herself.

And maybe that's what I find so compelling about this image. It suggests that vanity isn't separate from life—it's woven into it. The mirror isn't an escape from reality; it's part of how we navigate reality. We look at ourselves not just out of narcissism, but out of a basic human need to confirm our own existence, to check that we're still here, still recognizable to ourselves. Maybe vanity was never about thinking too highly of ourselves. Maybe it was about taking responsibility for the self we're given, this body and face and presence that we're somehow supposed to shepherd through a lifetime. We are, after all, the only project we're guaranteed to work on from birth to death.

I think about the hours I've spent in front of mirrors over the years—not just the quick glances, but the real sessions. Trying on different expressions, different ways of holding my face, different versions of who I might be. As a teenager, I'd practice conversations in the bathroom mirror, watching my face as I spoke, trying to figure out how my internal experience translated into something others could see. Was I readable? Was I performing myself correctly?

There's something almost scientific about it, this relationship with our own reflection. We're conducting experiments in selfhood, testing hypotheses about who we are and how we appear. The mirror becomes a laboratory for identity, a place where we can observe the strange phenomenon of being both subject and object, both the one who looks and the one who is seen.

All of this really makes me wonder about the difference between vanity and self-awareness. Vanity, in its classical sense, was about the futility of caring for temporary things. But self-awareness—that's different. That's about understanding yourself as a being in the world, about recognizing your own agency and presence. When I look in the mirror and adjust my hair, am I being vain, or am I simply acknowledging that I exist in a visual world, that I take up space, that others will see me?

Because here's the thing: I am this body. I am these hands typing, this face that gets tired, this voice that changes depending on who I'm talking to. I am not separate from my physical self—I am my physical self, and my physical self is me. To neglect this relationship, to treat my body as just a vessel for my "real" self, feels like a kind of abandonment of the most fundamental project I've been given.

I remember reading once that we're essentially the only animals who can recognize ourselves in mirrors. Dolphins can do it, and some great apes, but most creatures see their reflection as another being entirely. There's something profound about this capacity for self-recognition—it's not just about vanity, it's about consciousness itself. The mirror test is literally a test of self-awareness. Can you recognize that the being looking back at you is you?

There's a moment in Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse where she writes about a woman looking at herself in a mirror and feeling "the thing that mattered." Not her appearance, exactly, but the fact of her own existence, her own consciousness looking back at itself. That's what I see in this photograph—not vanity as moral failing, but vanity as a kind of existential confirmation.

The mirror, it turns out, tells us the most honest lie we know. It shows us ourselves reversed, flipped, not quite as others see us, but close enough to matter. It's the closest we can come to stepping outside ourselves and looking back.

I think about social media now, about how we've digitized the mirror, made it social and public and endlessly multiplied. We take pictures of ourselves and post them, seeking that same confirmation of existence, but now we need others to hold up the mirror for us. We've outsourced our vanity, made it collaborative. The "selfie" isn't just about self-love—it's about self-proof. I was here, each image says. I existed in this moment, in this light, with this expression.

But there's something lost in that translation from private mirror to public screen. The bathroom mirror doesn't judge; it just reflects. It doesn't keep score or compare you to anyone else. It's a moment of solitude, of private reckoning with your own image.

We see this same thing happening with the way we talk about "self-care" now, how we've medicalized the basic act of paying attention to ourselves. But taking care of ourselves isn't just about bubble baths and face masks. It's about this deeper work of witness, this patient attention to the self we're continuously creating.

But what fascinates me most is that moment of non-recognition I mentioned earlier, when I catch my reflection and feel genuinely surprised. If self-recognition is such a fundamental capacity, why do I sometimes fail at it? Why do I sometimes look at myself and think, Who is that person?

Maybe it's because we're not actually static beings. Maybe the self we're looking at in the mirror is genuinely different from the self we were the last time we looked. We're always changing, always becoming, always in the process of constructing and reconstructing who we are. The mirror doesn't just show us our appearance—it shows us our current iteration, our most recent draft.

The woman in this photograph seems to understand this. She's not just looking at herself—she's checking in with herself. She's taking inventory. She's seeing who she is today, in this moment, in this light, in this impossible room that spans centuries. There's something tender about her attention, something that suggests she's not judging what she sees, but simply witnessing it.

The mirror becomes a place of dialogue, then. Not just a tool for checking our appearance, but a space for conversation with the self we're becoming. How are you doing? we might ask our reflection. What do you need? How are you changing? What are you carrying that you could put down?

I guess we're all, in some sense, self-portraits. We're constantly making choices about how to present ourselves, how to be in the world, how to express the internal experience of being alive. Every day, we're adding brushstrokes to the ongoing work of art that is our lived existence. The mirror is just one of the places where we can step back and see what we're creating.

The woman in the photograph, with her classical posture and her presence in a modern room, reminds me that this work of self-creation is both ancient and ongoing. She's not performing for anyone but herself. She's not seeking approval or validation. She's simply engaged in the ongoing project of being human, of inhabiting a body, of existing as both consciousness and flesh.

As beautiful as they are, the classical vanitas paintings got it backwards, I think. They were so focused on the futility of beauty that they missed its necessity. We don't look at ourselves because we think we'll last forever—we look at ourselves because we won't. Because this face, this body, this particular way of being in the world is temporary and precious and deserving of attention, not despite its impermanence, but because of it.

I want to reclaim the mirror as a tool of self-knowledge rather than self-judgment. I want to look at myself with the same patient attention I'd give to a painting or a sunset—not because I think I'm perfect, but because I'm here, because I'm real, because this temporary arrangement of flesh and bone and consciousness is the only way I get to experience the world. Because the mirror doesn't lie to us—it shows us exactly what we've created so far, and invites us to consider what we might create next.

How did I get in here? I think when I catch my reflection unexpectedly. But maybe the better question is: What am I going to do now that I'm here? Or maybe even, what will any of us do when we’re finally seeing ourselves clearly?

XO, STEPF

Stepfanie, I’ve just discovered your essays… you’re brilliant. It’s like you’ve uncovered the thoughts in my head that I was struggling to understand. I look forward to what insights you will reveal to me next. And thank you.

What a lovely essay. Very thought provoking...