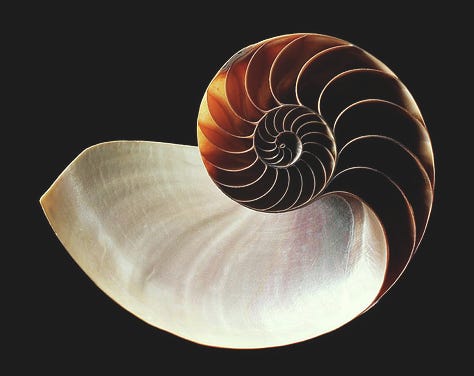

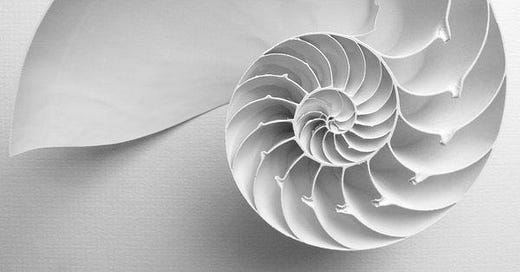

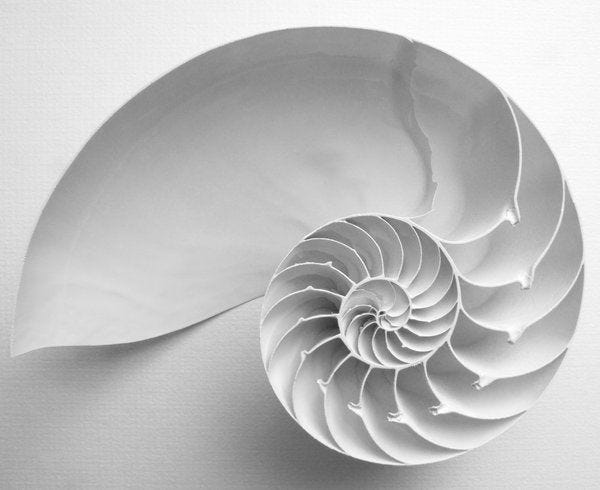

Seashell in hand, tide crawling up the sand, you notice the spiral tracing itself toward an invisible center—tightening, tightening, until it feels less like ornament and more like a blueprint. You don’t need a ruler to know it’s right. The eye settles. The body settles. Some quiet part of you recognizes the fit before the mind names it.

Later you learn the ratio of each turn shades closer and closer to φ, the golden proportion. A precise fraction hides inside a child’s beach souvenir, and your body—some old instrument of pattern recognition—spotted it before the calculator did.

That’s what I mean by beauty-as-truth. It isn’t decoration; it’s resonance. A click you feel in your bones when arrangement outruns explanation.

Like the seashell, some structures feel beautiful before you can explain why. Not decorative-beautiful. Not sentimental. A kind of clean alignment that the body recognizes before the mind catches up. Real beauty isn’t a reward for understanding. It’s the first breadcrumb. The early sign that something underneath is working. Order.

Euler’s identity, often called "the most beautiful equation," was celebrated not because it "felt good," but because it bound together five fundamental mathematical constants in a single line. A line so simple and inevitable that it made mathematicians feel, for a moment, like they were glimpsing the structure of the universe itself.

Euler’s identity, e^(iπ) + 1 = 0, still makes grown mathematicians flush.

Five primal constants, linked in a single line, like they were always meant to meet.

Nobody proved it beautiful; they just saw it and knew.

Physicist Paul Dirac once said he trusted equations that looked elegant, even when the data lagged behind. And history kept rewarding that aesthetic hunch: special relativity, quantum electrodynamics, hidden symmetries. The best theories didn’t just work. They looked right.

Form whispered first. Experiments caught up later.

Even after the proofs arrived, the sense of wonder stayed. Benjamin Peirce, a 19th-century mathematician at Harvard, once said of Euler’s identity:

"It is absolutely paradoxical; we cannot understand it, and we don’t know what it means, but we have proved it, and therefore we know it must be the truth."

There’s a pattern: symmetry, brevity, unexpected unity. When those three walk into the same room, smart people start taking notes.

Truth leaves breadcrumb spirals. Fern leaf, bronchial tree, lightning fork, river delta—self-similar explosions repeating at new scales, sketching the same riff until a forest looks like a pair of lungs and a coastline shares a pulse with a neuron. You don’t get an instructional manual telling you “this is optimal surface-area to volume.” You just stare and think of course. Beauty got there first.

Picture a coastline from above: jagged bays, peninsulas, inlets repeating like looped handwriting. Zoom in to a river delta, further into a lung’s bronchial tree, further still to a fern frond—all riffing on the same branching algorithm. Fractals aren’t a designer’s whim; they’re the cheapest solution to "maximize surface area in limited volume," exactly the problem lungs and deltas share. Your eye senses the optimization before the math chalks it out.

That sense can be cultivated. Turn a child loose with a magnifying glass in a garden and they’ll stumble on Fibonacci spirals half the afternoon—sunflower heads, pinecones, aloe rosettes. Adults call it botany; kids just call it pretty. Both labels describe the same event: order waving from behind the curtain.

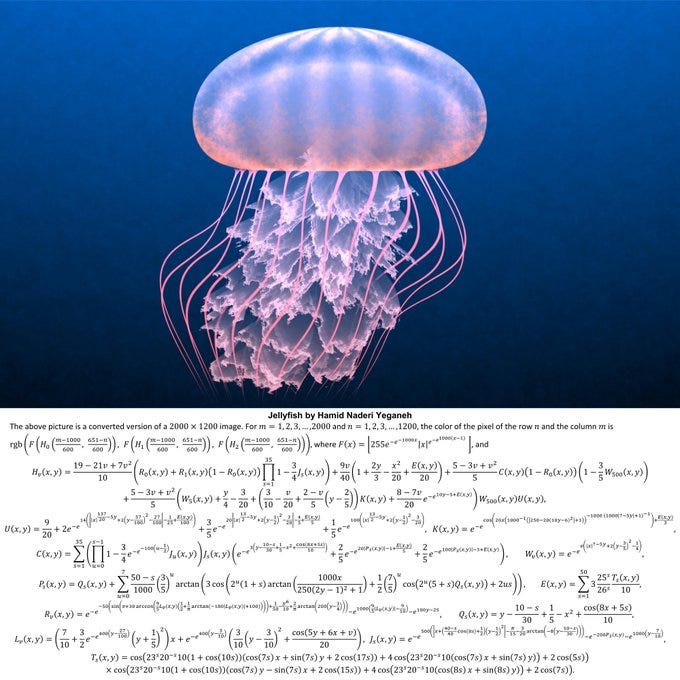

I remember the first time I saw one of Hamid Naderi Yeganeh’s mathematical images. A jellyfish made entirely from equations. Painted not by brushstrokes, but by math alone.

I stared at it for almost an hour. Kept coming back to it days later, like an itch I couldn’t quite scratch. It shifted something inside me—not because it was "pretty," but because of what it implied.

That maybe beauty isn’t just decoration layered onto the world. Maybe it’s written into the source code. Maybe the universe doesn’t just behave mathematically. Maybe it is mathematics. Not metaphorically. Literally.

That's the thing about mathematical beauty. It isn’t subjective polish. It’s structural coherence rendered visible.

You don't fall in love with the equations themselves. You fall in love with the coherence they reveal.

The spiral of a galaxy, the tendril of a river, the folds of your own lungs—it’s all math.

And when you spend enough time thinking about systems—physics, cognition, even simulation theory—you realize math isn't just the tool we use to describe the world. Math is the world.

Think of meeting someone whose presence just feels true: posture aligned, gaze steady, laugh placed where silence needed relief. You can’t cite a peer-reviewed why; the moment is simply right-angled. Weeks later you’ll discover their habits run on discipline and their words stack with integrity, but the first signal was aesthetic coherence—the same coherence you sensed in the seashell.

Psychologists talk about thin-slice judgment: humans form accurate readings of trustworthiness within seconds. The mechanism is pattern match—does posture match tone? Does micro-expression sync with speech rhythm? When it does, we label the total package "attractive," though the attraction is often cognitive more than carnal. Beauty of conduct predicts relational truth: this one will probably do what they say.

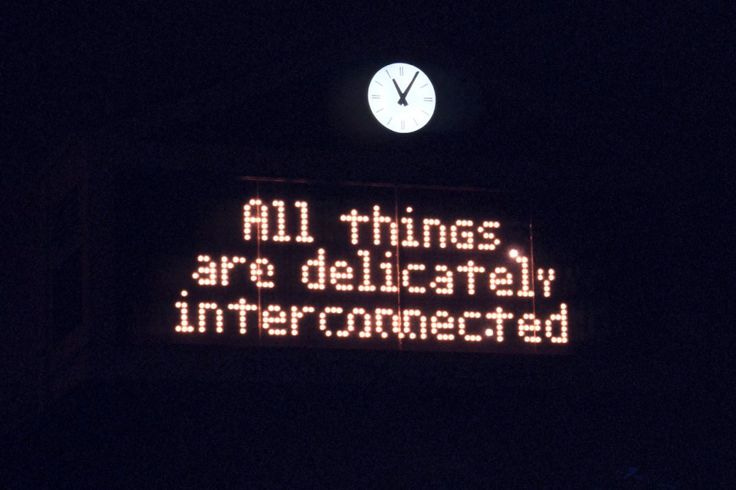

Beauty, real beauty, is a signal. It’s not decoration. It’s not marketing. It’s early contact with something aligned—something that fits into a deeper order even before it can be diagrammed.

You don't sense it because you're naive. You sense it because your body and mind are tuned, however imperfectly, to coherence. To proportion. To the kind of clean complexity that systems eventually confirm.

There’s a book called Why Beauty Is Truth that gets into this—tracking how beauty kept showing up first across history’s biggest scientific leaps. The elegance of Newton’s laws. The symmetry of special relativity. The spiral forms hidden inside chaos theory. Again and again, beauty wasn’t the reward after the fact. It was the clue.

And it doesn’t stop at physics.

You feel it when a piece of writing lands more cleanly than you expected. When a song opens up a corner of your brain that words couldn’t touch. When you meet someone and their way of being in the world strikes you as right before you know anything else about them.

You know it before you know it.

Neuroscience gets pragmatic here: the visual cortex fires more efficiently on proportionate inputs. Symmetry is cheaper to compress, so the brain rewards it with a micro-dose of dopamine. Evolution hacks attention; beauty is the bribe. That bribe steered early humans toward ripe fruit, healthy mates, and sturdy shelters. It still steers us toward clean code, satisfying melodies, and architectural lines that feel obvious once you stand inside them.

This isn’t metaphysics; it’s biology. Drop people inside an MRI and show them golden-ratio rectangles versus random ones—oxygen uptake tells the story. The neat shapes light up reward circuitry the way sugar used to before corn syrup ruined the metric. The brain likes patterns it can file quickly. Beauty is the label on the folder.

But filing speed is only half the story. The second half is resonance across scale. A logarithmic spiral crops up in a nautilus shell, a hurricane, and an interstellar nebula. See the same motif at three wildly different magnitudes and the mind suspects a rule, not an accident. Beauty is the hunch that the universe, while enormous, is internally consistent.

That hunch has a track record.

I’m reluctant to source my metaphysics to committee, but ditching the sacred entirely feels like bad accounting. Every culture that lasted past three harvest cycles kept some ritual around beauty and symmetry: hymns, mandalas, sand paintings, stained glass, raku pottery. The form shifts; the impulse doesn’t.

Beauty seems to function as a thin place, letting ordinary matter hint at unobservable structure—call it Logos, Tao, source code, whatever label offends you least. Einstein described “the mysterious” as the cradle of art and science; Emily Dickinson said “find ecstasy in life; the mere sense of living is joy enough.” Both were talking about the same thing: consciousness brushing up against order larger than the local plotline.

Some pushback is inevitable: tastes differ; cultures disagree; isn’t beauty just a bourgeois ornament? Fair, to a point. Gothic spires thrill some, brutalist slabs thrill others. But the disagreement usually lives at layer two—style. The underlying heuristics (symmetry, proportion, unexpected unity) remain shockingly constant across epochs. Your brain can admire both a Zen garden and a Cimabue crucifix because each obeys its own strict internal logic. Truth wears more than one outfit.

The mistake people make is thinking beauty is superficial. That because it shows up early, it must be suspect. That because it’s emotional, it must be irrational. But beauty isn’t irrational. It’s pre-rational. It’s the early light before the full mechanism comes into view.

Beauty is truth’s first breadcrumb, not its last ornament.

I didn’t write this piece to preach aesthetics. I wrote it to remind you that the next true thing will probably arrive disguised as something unreasonably lovely.

When it shows up lopsided, luminous, undeniable—trust it. Move toward it. Let the spreadsheets catch up later.

st: "share this with someone who is undeniably beautiful 🌹"

me: done; i shared it with myself.