thoughts on ego involvement and the weight of being

reframing how we see and engage with our work

Quick note before the essay: I have a couple of new projects launching for my paid readers, one of which includes a weekly Sunday newsletter “last week in the wild”. I was planning on launching it this past weekend, but life happened. My 2 yo puppy got injured last week and I’ve been dealing with that since. Spent most of yesterday at the vet doing X-rays and other super fun stuff. She’s still recovering from all the sedation, but they started her on pain meds for her injury and hopefully she’ll be on the mend soon. All to say—I write most of what I share in real time and occasionally life throws itself at me in unexpected ways and plans fall through. Part of being human. Anyway! Keep an eye out for some fun new stuff in the next couple of weeks—and a huge THANK YOU to all my readers, especially my paying subs… your support and belief in my work seriously means the world to me. Ty ty ty! ❤️🔥

I'm sitting here, staring at a blank page again, and I can feel that familiar tightness in my chest—the one that comes when the cursor blinks expectantly and I know that what I write next will somehow reflect back on who I am as a person. Not just as a writer, mind you, but as a person. As if these words might reveal some essential truth about my worth, my intelligence, my right to take up space in the world.

This is what the psychologists call "ego involvement," though they say it with the clinical detachment of people who've never felt their entire sense of self hanging on whether a particular sentence lands well. Leon Festinger wrote about it in the 1950s, this phenomenon where our identity becomes so entangled with our performance that failure stops being just failure—it becomes a referendum on our very existence.

I think about this often, probably more than is healthy. How many projects have I abandoned not because they were too difficult, but because they became too important? How many times have I found myself paralyzed by the weight of my own caring, frozen between the desire to create something meaningful and the terror of revealing myself as fundamentally inadequate?

There's something almost absurd about it when you step back. Here I am, a creature that has somehow stumbled into consciousness on a spinning rock in an infinite universe, and I'm worried about whether my attempts at expression will confirm that I'm worthy of... what, exactly? Love? Respect? The basic right to exist without apology?

But the brain doesn't care about cosmic perspective when it's trying to protect us from social death. That ancient machinery, evolved when being cast out from the tribe meant literal death, doesn't distinguish between "my essay was poorly received" and "I am in mortal danger." It just knows that something precious—our sense of belonging, our place in the hierarchy—is at stake.

I'm reminded of Martha Graham, the dancer and choreographer who revolutionized modern dance in the 20th century. She once said, "All that is important is this one moment in movement. Make the moment important, vital, and worth living. Do not let it slip away unnoticed and unused." What strikes me about this isn't just the focus on presence, but the implicit understanding that the moment itself—the work itself—is where the meaning lives. Not in what it says about us, but in what it is.

This is where ego involvement becomes not just psychologically destructive but almost philosophically backwards. When I make my identity dependent on outcomes, I'm essentially arguing that my worth is determined by things largely outside my control—how others receive my work, whether the market rewards my efforts, whether I happen to be talented enough or lucky enough or born into the right circumstances. I'm taking the most intimate thing I have—my sense of self—and handing it over to external forces, then wondering why I feel so anxious all the time.

The paradox is that this attachment to outcomes often produces exactly what we're trying to avoid. I remember reading about Yo-Yo Ma, the cellist, describing how his best performances came when he stopped trying to prove himself and started simply serving the music. When he shifted from "How do I show everyone I'm a great musician?" to "How do I honor this piece of music in this moment?" something fundamental changed. The ego stepped aside, and excellence emerged not as a by-product of self-promotion but as a natural consequence of attention and care.

But here's what I find most interesting: it's not that we need to stop caring. If anything, the people who create meaningful work tend to care more than average, not less. The difference is in where they direct that caring. Instead of caring about being seen as good, they care about doing good work. Instead of caring about avoiding failure, they care about learning from it. Instead of caring about maintaining an image, they care about engaging honestly with reality.

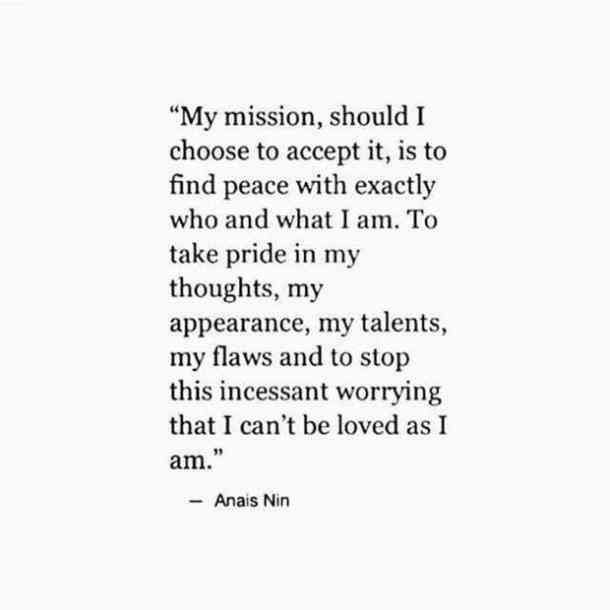

I think of Anaïs Nin, writing in her diary: "The risk it takes to remain tight in a bud is more painful than the risk it takes to blossom." She understood something essential about the relationship between vulnerability and growth. When we wrap our identity so tightly around our achievements, we create a kind of psychological constriction that makes it almost impossible to take the very risks that growth requires.

I think this is why children are such natural learners. Before they develop a fully formed sense of ego, before they learn to measure themselves against others, they approach new challenges with a kind of fearless curiosity. They fail constantly and magnificently, dust themselves off, and try again. Not because they don't care about the outcome, but because they haven't yet learned to make the outcome mean something about their fundamental worth as beings.

There's a Zen saying I keep coming back to: "You are perfect as you are, and you could use a little improvement." It captures something essential about this dance between acceptance and growth. The first part—you are perfect as you are—isn't about complacency or lowering standards. It's about recognizing that your worth isn't conditional on your performance. The second part—you could use a little improvement—isn't about inadequacy. It's about the natural human impulse toward growth and learning.

When I can hold both of these truths simultaneously, something interesting happens. The work becomes lighter, somehow. Not because I care less about quality, but because I'm no longer carrying the additional weight of my entire self-concept along with it. I can focus on the actual task at hand rather than the meta-task of proving myself worthy of attempting it.

I'm reminded of something the writer Anne Lamott said about her writing process: "Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere." There's such wisdom in that "somewhere"—not "start perfectly" or "start impressively" or "start in a way that validates your decision to call yourself a writer." Just start somewhere. Trust the process. Let the work teach you what it wants to become.

This shift—from proving to exploring, from performing to practicing—requires a kind of faith that feels almost radical in our achievement-obsessed culture. It requires believing that the work itself has value independent of how it reflects on us. That learning has value even when it happens through failure. That engagement itself is a form of success, regardless of outcome.

I'm still learning this, probably will be for the rest of my life. There are days when I can feel myself slipping back into that old pattern, when the weight of my own expectations makes even simple tasks feel impossible. But there are also moments—usually when I'm most absorbed in the work itself—when I catch a glimpse of what it might feel like to create without the burden of self-justification. Those moments feel like coming home to myself.

Maybe that's what this essay is really about: the journey from "What will this say about me?" to "What does this want to become?" From "How can I prove I'm good enough?" to "How can I be present enough to do justice to this moment, this challenge, this opportunity to engage with something larger than my own small anxieties?"

The work is still there, waiting. It doesn't care about my reputation or my insecurities or my carefully constructed sense of self. It just wants to be done, with whatever skill and attention and love I can bring to it right now, in this moment, imperfect and human as I am.

So, here’s to doing the work—and remembering, no one is really watching anyway.

See you soon xo

catch up on last week’s reading —

there's always that one person who feels like unfinished business

I’ll be honest, I’ve had this post saved in my drafts for a while now—I keep chickening out when it comes to sharing it, but I …

don't take it personally, it wasn't even about you

Last weekend, something curious happened to my nervous system. One of my Substack essays had what people generously call "gone viral"—hundreds of comments flooding in, most of them thoughtful, encour…

Very well done. Reading through this, all I could think of was one of the pianist playing on the recording of Bob Dylan's epic song, Murder Most Foul.

Fiona Apple told Dylan she felt insecure playing on the track. Dylan responded by saying words to the effect; you're not here to be perfect, you're here to be you.

Easily you have become my fave morning coffee read.