I've started sleeping with the dead.

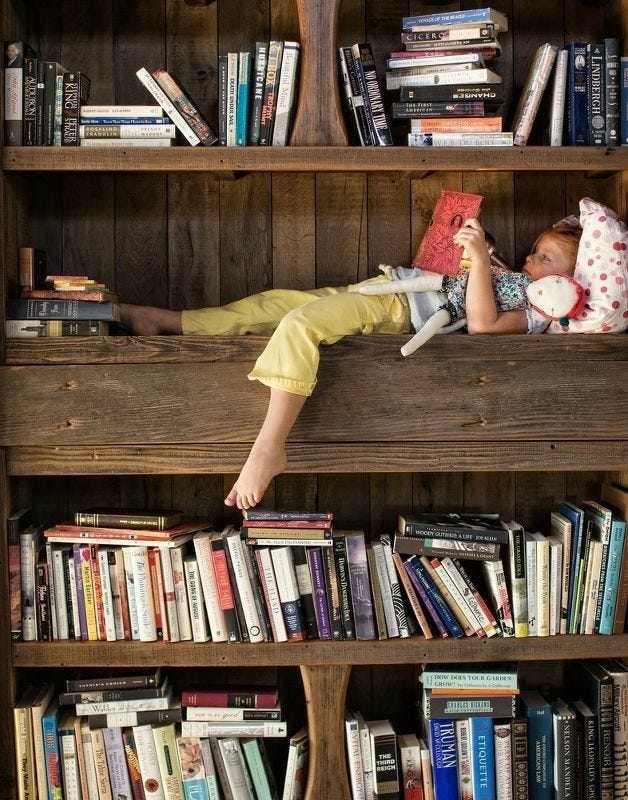

Not in the morbid way that sounds, but in a way that feels both ancient and strangely intimate. Last weekend, I moved all my literature and art books from my office into my bedroom, arranging them on shelves that face my bed. It wasn't a decorating decision. It was something more primal—this inexplicable need to be physically near them as I drift in and out of consciousness each day.

This morning, I woke up and stared at them before even checking my phone (a small victory these days). There they were: Homer, Dante, Woolf, Morrison—a constellation of minds spanning millennia, all within arm's reach of where I lay tangled in my sheets, halfway between dreams and waking. There's something thrilling about this realization. I'm sleeping beside the oldest stories ever told, breathing the same air as words that have survived empires.

It's ridiculous to feel this way about objects, I know. They're just paper and ink and glue. Products. Commodities. Yet I can't shake the feeling that they're something more—that they're alive in some paradoxical way, both dead (their authors long gone) and pulsing with a persistent, patient kind of life.

The Scent of Time

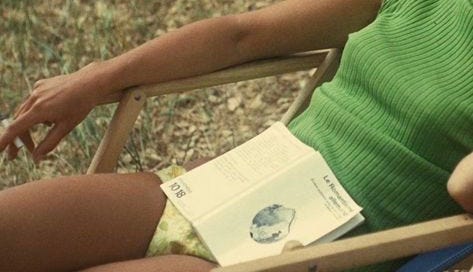

Yesterday, I thrifted a 1950 "deathbed edition" of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. The book is nothing special from a collector's perspective—not a first edition, not particularly rare, the spine slightly cocked, the pages yellowed at the edges. But when I opened it and brought it to my face (a reflexive gesture I've performed with books since childhood), something extraordinary happened.

I inhaled, and suddenly I was six years old again, standing in my grandfather's living room in the eucalyptus-covered hills outside town. The woody, vanilla-tinged scent of the aged paper triggered something so visceral that for a moment I could feel the texture of his stone floors beneath my feet, hear the soft pop and hiss of the ever-burning fire in his hearth, see the way the California light filtered through those high windows and caught the dust motes swirling above his own overstuffed bookshelves.

My grandfather has been dead for years now. His house belongs to strangers. But somehow, impossibly, here he was—conjured by what scientists clinically call "bibliochor," the distinctive aroma produced by the breakdown of lignin and cellulose in aging paper. This chemical process released compounds similar to vanilla, almond, grass, and must—the same compounds present in his wooden house with its stone hearth and eucalyptus grove.

I sat on the edge of my bed, a little disoriented by this temporal collision. Here was the past (my grandfather's house) meeting another past (Whitman's final revisions before his death in 1892) in my present moment, all through the medium of this ordinary object. The same scent molecules that entered my six-year-old lungs were entering my thirty-six-year-old lungs now, like some impossible form of time travel.

And isn't that what books are? Time machines disguised as rectangles?

Whitman's Body/My Body

Holding this particular time machine feels especially significant. Whitman spent nearly four decades revising Leaves of Grass, publishing it first in 1855 and continuing to expand and reshape it until his death. This "deathbed edition" represents the final iteration of that lifelong conversation with himself—the culmination of a poet's evolving vision.

I find myself running my fingers along the edges of pages that other fingers touched decades before mine. Someone in 1950 held this exact book, opened to this exact page where Whitman declares:

"I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul,

The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me,

The first I graft and increase upon myself, the latter I translate into a new tongue."

There's something almost unbearably intimate about this—about the physical transmission of these words through time via this specific object. The book itself has a body that ages, that carries its history in visible marks and invisible scents. It has known other hands, other rooms, absorbed other environments before arriving in mine.

I wonder about the forgotten choreography of gestures that delivered it here: the hands that packed it for shipping, that organized it on a used bookstore shelf, that perhaps inherited it from a parent or grandparent who first purchased it in 1950. Did someone pack it away in an attic where it absorbed the particular chemistry of that enclosed space for decades? Did it sit on a shelf near a window where sunlight gradually yellowed its pages? Was it read outside where pollen might have settled between its pages?

I'll never know these things, yet somehow the book carries these invisible histories in its physical being—histories I'm now incorporating into my own as I add my oils, my skin cells, my environment to its ongoing material life.

The Library of Breath

Sometimes I imagine all the breaths that have passed over the pages of the books surrounding my bed. The medieval monk breathing on his illuminated manuscript, the Renaissance woman secretly reading by candlelight, the Victorian family gathered around a single volume read aloud, the mid-century office worker unwinding with a paperback on his commute home.

All those exhalations—carrying the microscopic evidence of meals eaten, air polluted or clean, bodies healthy or ill—all those intimate exchanges between reader and page accumulating in the physical matter of the book itself. We think of reading as an intellectual exchange, but it's also this profoundly physical communion across time.

I realize this sounds mystical, maybe even a little unhinged. I'm anthropomorphizing paper and ink. I'm romanticizing what are essentially consumer products. But I can't help feeling that there's something sacred in these physical vessels of thought that machines can't replicate.

My Kindle doesn't smell like my grandfather's house. Audiobooks don't carry the history of previous listeners in their digital encoding. The words may be identical, but something is lost in translation—something about the embodied nature of both books and humans.

Whitman understood this. "I am the poet of the Body," he insisted, refusing to separate the physical from the intellectual, the corporeal from the spiritual. He celebrated the body as the necessary vessel for consciousness, for connection, for meaning—just as the physical book is the vessel for his words.

Sleeping Beside Multitudes

There's a line from Whitman that's been floating through my mind since I rearranged my bedroom: "I am large, I contain multitudes." It's one of those quotes that's become almost too familiar, printed on coffee mugs and Instagram graphics, divorced from its original context in "Song of Myself."

But as I lie in bed, looking at the spines of all these books lined up just a few feet away, I'm struck by the literal truth of it. These books contain multitudes—not just of ideas or characters or worlds, but of actual people who shaped them, touched them, breathed on them.

What does it mean to choose to sleep beside these multitudes? To make my most vulnerable space—the place where I dream, where I drift in and out of consciousness, where I am most defenseless—also the place where I keep these vessels of other consciousnesses?

I'm not sure, but it feels significant. It feels like a recognition that reading isn't just an intellectual activity but a form of communion. That books aren't just vehicles for information but physical links in a chain of human connection stretching back to our earliest attempts to make meaning.

My grandfather's library was a defining feature of his home—floor-to-ceiling shelves that I remember looking up at in childhood awe. When he died, his books were dispersed among family members, sold to used bookstores, donated to libraries. I have a few volumes from his collection, their margins filled with his slanted handwriting, evidence of his dialogue with authors long dead.

Now I wonder if some stranger somewhere is breathing in the scent of one of his books and being transported to a place they've never been. I wonder if some molecule from his hand, his breath, is traveling forward in time through the medium of those pages, creating connections he never could have imagined.

The Weight of What Remains

My copy of Leaves of Grass isn't particularly heavy—a medium-sized hardcover, nothing like the massive art books sharing the shelf with it. But it carries a different kind of weight.

It carries the weight of Whitman's relentless revisions, his determination to create a work that could contain his expanding vision of America and humanity. It carries the weight of its journey through seventy-five years before reaching my hands. It carries the weight of my unexpected emotional response to its scent, the memories it unlocked.

Books are technologies, yes—inventions designed to transmit information across space and time. But unlike our newer technologies, they don't try to escape the physical world. They don't pretend to be frictionless or immaterial. They embrace their objecthood, their vulnerability to water and fire and time. They accumulate history visibly—in coffee stains and dog-eared pages, in broken spines and faded covers.

And maybe that's why sleeping near them feels so right to me now, at this moment in my life. They remind me of my own materiality, my own accumulating history. They remind me that meaning doesn't exist in some pure, abstract realm but is always embedded in specific, physical forms.

Tonight, I'll place this 1950 edition of Leaves of Grass on my nightstand. I'll probably open it again, breathe in its particular chemistry once more, feel that disorienting collapse of time and space. Then I'll turn out the light and sleep beside it—one body resting near another body, both containing multitudes, both translating our experiences "into a new tongue."

And somewhere, perhaps, Walt Whitman would approve of this strange intimacy across time, this communion of bodies and words, this ongoing conversation between the living and the dead.

As always, thanks for reading with me. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the like button and/or sharing it to help boost its visibility.

I appreciate you so much. xo

wow… the mental imagery this one created. I loved it