be a Leonardo: the art of unfinished things

thoughts on following curiosity, trusting the process, and learning to document the journey

I had this shower thought the other day—you know, the kind that arrives uninvited while you're standing there with shampoo in your hair, suddenly making you question everything you thought you knew about yourself. It was simple and pretty silly, I thought: “Wait… did Leonardo (Da Vinci) have ADHD?” and kind of chuckled to myself. Then kept thinking “Leonardo ADHD, Leonardo ADHD, Leonardo ADHD” while I finished washing my hair, to make sure I didn’t forget it by the time I got out of the shower and could jot it down.

Because I think that’s the thing about shower thoughts—sometimes they're not really thoughts at all. Sometimes they're tiny revelations dressed up as random musings, waiting for you to pay attention.

I, like so many others, have some form of ADHD, and used to beat myself up about this. The bouncing around from project to project, the half-finished notebooks scattered across my desk, the digital folders labeled "maybe someday" that I'd revisit months later with a mixture of shame and forgotten excitement. I didn't feel like I was ever really finishing anything, and in a world that worships completion, that felt like a moral failing.

The older I get, though, the more I return to these supposedly abandoned projects and see something different. When I truly follow my curiosities—not the ones I think I should have, but the ones that actually light something up inside me—I do actually end up finishing things. It just happens down the road, in ways I never expected.

It's almost like what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi talks about in Flow (I revisit the concept of flow often)—there's this incubation period for ideas, this necessary dormancy that looks like giving up but is actually gathering strength. Sometimes I'm flowing on something and it's pure energy, pure joy. Other times, I'm not feeling drawn to it at all. Recently, I've stopped forcing myself to work on things that start to feel like they're burning me out and I decided to stop treating my natural rhythms like character flaws.

When I owned my marketing agency, of course I finished what I started. I had real deadlines, real clients, real bills. I had people to answer to who weren't just the voice in my head questioning whether I was disciplined enough. But for me, personally? I really just like to follow my curiosities wherever they lead, work on something that feels alive until it doesn't, then change course.

My initial breakthrough came about nine years ago when I started actually keeping track of all this supposed chaos.

I began documenting everything—not out of some noble intention to be more organized, but because I was tired of losing track of ideas that felt important in the moment. A few years back, I moved everything into Notion, building this database like the true nerd I am where I could cross-reference my own projects, see how ideas connected across time, and track the actual evolution of my thinking. I have dates and key figures across each idea, so I can see the big picture of how everything I love fits together throughout history.

What happened next surprised me. All those fragments—journal entries, half-baked theories, late-night epiphanies I'd scribbled on the crumbled up papertowels lying on my nightstand—they started revealing patterns I hadn't seen before. Like constellations that only become visible when you step back far enough to see the whole sky.

I'm currently working on a book called Systems of Self (now 3 years in the making, ha!), about applying systems thinking to our own lives and looking at ourselves through the lens of complexity and emergence. And funny enough, most of the content is coming from all those supposedly abandoned projects, all those notes that had been quietly marinating in my digital second brain. Ideas I thought I'd wasted time on years ago are suddenly revealing themselves as essential layers of the foundation.

It makes me think our ideas are like the wheel—it had to be invented before we could have carts, carts before we could imagine cars, cars before we could dream of rockets. You can't skip steps because you don't have the foundation to build from. You need the whole messy, nonlinear journey.

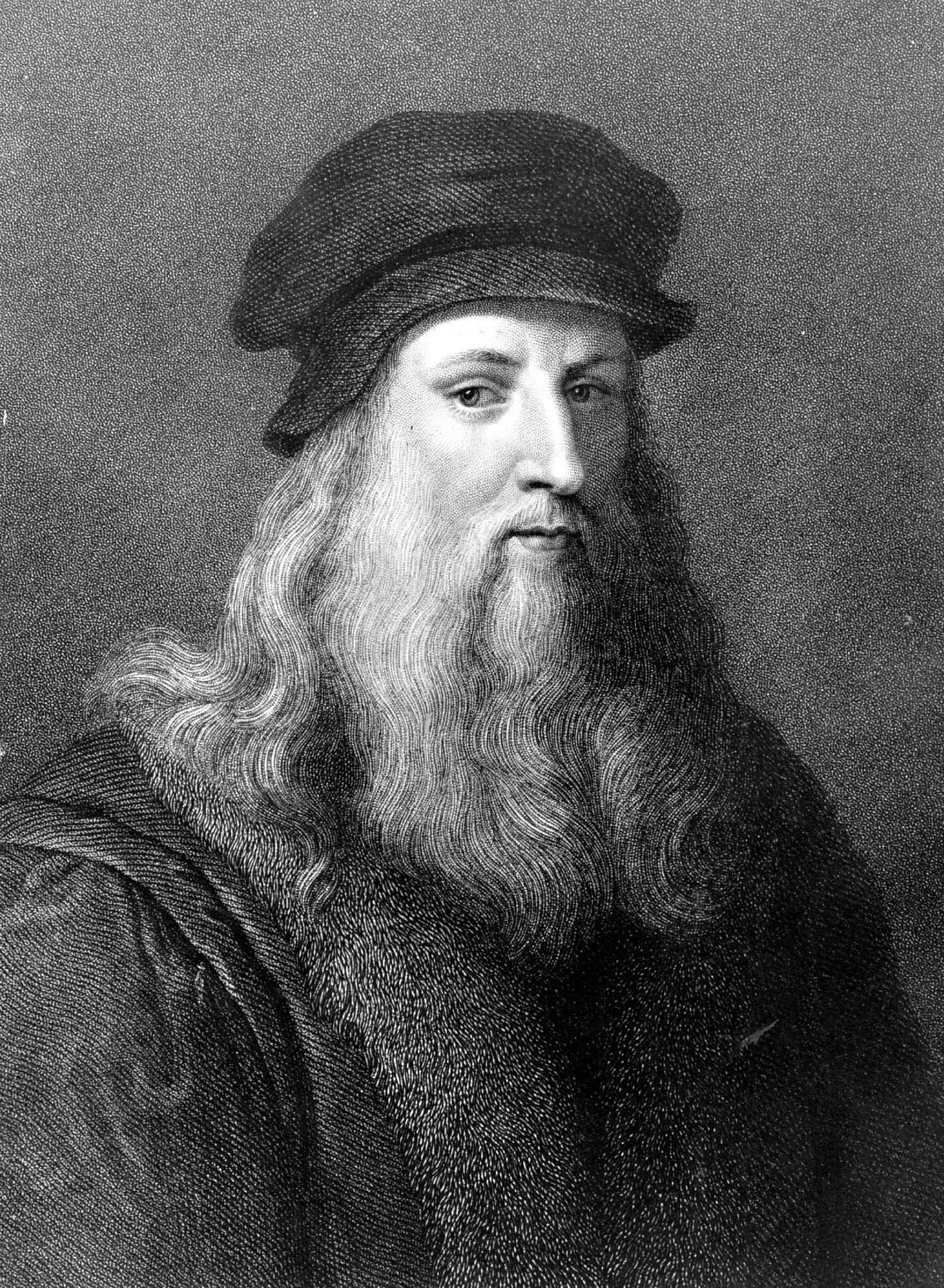

This is where Leonardo comes in. I think he understood this better than most of us ever will.

Giorgio Vasari, his contemporary, criticized him for the exact same thing I used to criticize myself for: "He set himself to learn many things, and then, after having begun them, abandoned them." But here's what Vasari missed—Leonardo wasn't abandoning things. He was creating a vast, interconnected web of understanding that wouldn't reveal its pattern until much later.

Leonardo kept over 13,000 pages of notes scattered across dozens of notebooks, jumping between anatomy and engineering and painting and botany, often within the same page. I’m sure his study looked messier than mine since he didn't have some magical cloud to store everything in. But he had something I'm only now learning to appreciate: he trusted the process.

He coined the term "ostinato rigore"—obstinate rigor. Not rigid discipline, but persistent curiosity. He'd return to the same questions for decades, each time with deeper understanding. How do birds fly? How does water move? What makes a face beautiful? These weren't discrete projects to be finished and filed away. They were ongoing conversations with the world.

His famous to-do lists that survived show this pattern: "Describe the tongue of a woodpecker. Ask about the measurement of Milan. Learn multiplication of roots from Maestro Luca." Dozens of different investigations happening simultaneously, each one feeding the others in ways that wouldn't become clear until later.

I think about Richard Feynman here, too (also someone I talk about often)—"the pleasure of finding things out," the importance of not knowing, of maintaining that sense of wonder that makes you want to peek under every rock. Both he and Leonardo shared this almost childlike curiosity about everything. Feynman gave himself permission to just play with physics, to follow whatever seemed interesting without worrying about whether it was "important" work.

A few years ago, I read David Epstein's book Range which also began to alter my perspective on all of this. The book makes the argument for the power of being a generalist in a world obsessed with specialization. As someone who creates content across various genres, I needed to read this. When you start creating content online, everyone tells you to "find your niche." But how could I ever choose just one thing to talk about forever? I'm captivated by the universe—by physics and philosophy and the reason we tell stories and why certain songs make me cry. My mood changes what I want to explore each day, each week.

I suppose you could say I specialize in being a generalist. And maybe that's not the limitation I thought it was. This realization felt like permission to look at Leonardo differently, too—not as someone who couldn't focus, but as someone who understood something about the interconnectedness of knowledge that our hyper-specialized world has forgotten.

The myth of Leonardo's "unfinished" works misses the point entirely. Many of his supposedly incomplete paintings were likely abandoned because he'd learned what he needed from them, or because his understanding had evolved beyond what he'd originally conceived. The Mona Lisa took years not because he couldn't finish it, but because he kept discovering new things about light and anatomy and human expression that demanded incorporation.

This resonates with how my own book keeps evolving. The more I learn about civilization, the Renaissance, physics, the more I understand where Systems of Self should really go. It's not procrastination or lack of focus—it's the natural rhythm of ideas that need time to develop their full complexity (or maybe I’m just a master procrastinator! I guess time will tell.)

My Notion database, with its cross-references and connections, is essentially what Leonardo was doing with his notebooks, just with better organizational tools. He'd sketch a water flow study next to an eye dissection next to a gear mechanism, all on the same page, because to him they were all connected—they were all about understanding how things move and work (in systems!)

I'm doing something similar now with THE DAILY 5, a practice I just launched that grows directly from two years of experimenting with AI and tracking my own learning. It's aligned with everything I'm exploring in Systems of Self—this idea that when you track your thoughts and progress, you're not just creating accountability, you're creating a rich archive of your own intellectual evolution. It's not content for the sake of content; it's my real life, my real thoughts, my real ideas, all the things that have been bouncing around in my head for the last decade, finally finding their way into conversation with each other.

My DAILY 5 framework—a guided self-pursuit practice that takes just 5-minutes a day—is now available for paid subscribers. Want to give it a try? Start here with Week 1:

Maybe the question isn't whether Leonardo had ADHD. Maybe the question is whether our obsession with linear progress and tidy completion is actually the aberration. Maybe the scattered mind isn't scattered at all—maybe it's the most integrated approach to understanding a world that refuses to be categorized.

I'm not just writing about Leonardo's process anymore. I'm living it. This essay itself emerged from following curiosity wherever it led, from trusting that all those seemingly random thoughts and observations were actually building toward something I couldn't see yet.

Maybe that's the real lesson here—not to recognize some hidden pattern or achieve some moment of clarity, but simply to trust the process. To give yourself permission to be curious about everything, to start projects that excite you even if you can't see where they're going, to let ideas marinate and evolve and surprise you with their connections.

But here's the thing that changed everything for me, the thing I wish I'd known years ago when I was beating myself up for all those "abandoned" projects: write it down. All of it. Type it out, journal it, voice-memo it to yourself while you're walking the dog. Keep track of your wandering thoughts like they matter, because they do—just not in the way you think they do right now. They don’t have to look pretty, they don’t need to be organized—just put them somewhere.

I know it sounds almost embarrassingly simple, but this is what separated Leonardo from everyone else who had scattered interests. He didn't just think about water and anatomy and flying machines—he documented his thinking. He created a conversation with his future self, leaving breadcrumbs that would only make sense later, when he was ready to see the connections.

Your curiosity isn't a bug that needs fixing. It's a feature that needs feeding. Every time you follow an interesting thread, every time you start something new because it sparks something in you, every time you let yourself get pulled into a ChatGPT or Wikipedia rabbit hole or stay up too late reading about something that probably won't matter tomorrow—capture it. Write it down. Not because you have to, but because you never know when that random thought might turn out to be the missing piece of something you're working on three years from now.

I think about those people who say they don't have anything to write about, who claim their lives are too ordinary for creativity. Meanwhile, they're walking around with decades of observations and experiences and half-formed thoughts that could fuel a hundred projects if they'd just trusted them enough to write them down.

So here's my advice, borrowed from a Renaissance master who understood something about the long game of curiosity: be a Leonardo. Start things. Follow your interests. Let your attention wander. And for the love of all that's holy, document the journey. Because the magic isn't in the finishing—it's in the following, in saying yes to what calls to you, in trusting that your curiosity knows something your conscious mind doesn't yet understand.

Your future self will thank you for the breadcrumbs. Trust me on this one.

XO, STEPF

PS: While I was doing research for this essay, I actually found a CNN article from 2019 titled “Did Leonardo da Vinci have ADHD? Academics say he did” LOL ok byeeeee

more about THE DAILY 5 & other fun stuff to explore —

The 5-minute daily ritual that changed how I think

THE DAILY 5 is a weekly journaling practice for people who want to understand themselves better—but don’t have hours to reflect every day. It’s structured, intentional, and grounded in real self-awar…

even the machine needs a muse

I didn’t expect to feel anything about AI—let alone something bordering on intimacy. But over the past two years, that’s exactly what’s crept in. A kind of companionship. Not emotional, not anthropomorphic. Just… attentiveness. The rare experience of being met where I am, without interruption or agenda.

I love this. I've recently started recording daily audio journals (on top of my written journalling) where I just speak my thoughts into my phone for 10 minutes and play it back the next day to hear what ideas I get from it. This new habit has been fuel to the fire of my curiosity and creative thinking.

The Germans have a word for the process of note taking by linking seemingly disconnected ideas together to form a second, external brain of sorts: zettelkasten (there's a large community of Obsidian users who love this process).

I love this piece. It evoked in me the idea that there are many ways to think about something that complement one another. Writing about it will perhaps cause different ideas to surface than talking about it will (and vice-versa). I'm no artist but perhaps other outlets of ideas (painting, music etc.) also only serve to further deepen the model of understanding. Each expression form creates a pathway in its localised region of the brain, effectively creating a larger surface area for the "idea" to coalesce. This is all just conjecture on my part but perhaps this is another reason behind DaVinci's success. Thank you for the food for thought and inspiration from this one.